Yet Another NPPF on its Way?

What? Another One? If you think that the long-awaited revised version of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) wasn’t enough, we may well be faced with yet another version after the forthcoming General Election!

by Robert Gillespie, Managing Director | 22 March 2024

Planning practitioners have to be braced for what could well be yet another NPPF following a Labour victory after the next General Election. The current version[1], published shortly before last Christmas, turned out to be an essentially politically motivated attempt to shore up the core vote within the Conservative shires while giving the impression that the Government was determined to increase and maintain housing delivery.

Other than the confusion created within the national policy generated by an overly complex arrangement of paragraphs and footnotes (notably paragraphs 76, 77 and 226 and which then required the issuing of clarification within the Planning Practice Guidance (PPG)), regarding the calculation of 4- or 5-years’ worth of housing land supply, this NPPF has already generated overtly political reaction.

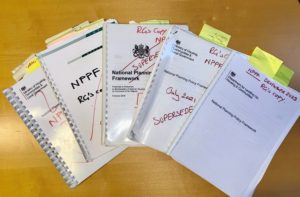

Superseded Revisions of the NPPF.

Not only is there evidence that some local planning authorities chose to stall the determination of perceived politically sensitive applications which would have otherwise benefitted from the “tilted balance” in favour of permission under the terms of the previous NPPF, but applications the subject of earlier resolutions to grant (pending completion of s.106 agreements), were returned to committee and refused in the light of the new national policy as the completion of the s.106 agreements had also been stalled.

These were, to all intents-and-purposes, applications which until very recently, were considered as not giving rise to any adverse impacts which would significantly and demonstrably outweigh the benefits as assessed against the NPPF.

The NPPF has in effect raised the status of the policies and proposals in an emerging development plan which has reached either the Regulation 18 or 19 stages which precede that plan’s examination. It had conventionally been the case that those policies of an emerging plan which were under challenge (typically housing) were not attributed significant weight in decision-taking until after the examination stage and the consequences of the Inspector’s report and recommendations had materialised. That is still reflected in national policy as say expressed at paragraph 48.

The intention which lay behind such a pragmatic approach was to ensure that only once the emerging plan had been examined and considered by an independent Inspector, could the surviving tested policies and proposals of the plan be regarded as sound.

This fundamental principle has now been breached. The new NPPF in effect presumes that such is the efficacy of the housing policies and proposals with an emerging local plan, that the requirement to provide and maintain a minimum of 5 years’ of housing land supply can be reduced to 4 years’ worth, before the examination stage has taken place. Given that the housing policies and proposals contained within most emerging plans tend to be THE more controversial, this is indeed a bold albeit temporary, change in policy.

The aim is clear. It is intended to reward a number of authorities already at the Regulation 18 or 19 stage and to stimulate other local planning authorities reluctant to get on with plan-making (many notable shire authorities have been stalling plan production) into action. As the measure is a temporary 2-year adjustment, it is seemingly more intended to assist with electoral prospects than pragmatism.

The risk however in all of this is that come the examination the housing policies of the emerging local plan are found unsound or in need of significant modification leading to protracted delays in bringing into effect adequate remedy. In the meantime, the four years’ worth of residential land supply will diminish resulting in another wave of speculative housing applications taking everyone back to square one. For those authorities placing reliance on delivery of housing numbers in the fifth year to get them over-the-four-year-line, this is even more serious.

Practitioners are all too well aware of how long, following the original grant of an outline planning permission (typically associated with larger residential schemes), it takes to achieve the necessary approval of reserved matters and then the extensive suite of pre-commencement conditions attached to either the outline and, or the reserved matters approval.

The entire delivery system is often significantly delayed beyond the initial outline permission due to the reliance placed by applicants and planning authorities on the statutory consultees to provide responses and ultimately “sign off” on the detailed proposals in good time. As with most local planning authorities, these consultees are under-resourced resulting in substantially longer time taken to achieve the necessary answers to enable granting reserved matters approval or the discharging of conditions precedent.

The Government may well intend to direct more resource toward the statutory consultees, as with the proposals for planning authority planning staff, however the time which this is likely to take will still not correspond with the backlog of housing applications awaiting determination and plan production.

While the reduction from a minimum of 5 to 4 years’ worth of supply may be politically appealing to those authorities which have reached the Regulation or 18 or 19 stages in the production of their plans, it appears unlikely to solve the underlying problems facing the English planning system. There is, as now widely acknowledged, also a chronic shortage of qualified planners. Those problems require far more robust thinking.

If there is a change in Government, will the new administration be capable of effective and rapid action sufficient to tackle these fundamental problems let alone a further version of the NPPF? I fear not, as such has been the structural damage caused to the system over the last 30 years that it will need time to recover anything like an effective system including regional strategic planning.

As an incoming Labour Government will be committed to maintaining strict control of the public finances and as that planning is at a relatively low position in any spending hierarchy, the ability to radically change the financial context for plan-making and decision-taking will be extremely limited.

Further increases in planning application fees seems inevitable adding to the already high cost associated with the preparation and submission of planning applications for all but the more modest householder application.

For small-to-medium sized building companies (historically associated with delivering substantial annual housing numbers) the sheer cost of the preparation of planning applications has increased significantly over the last 25 or so years. This is particularly so in relation to the extent of application material required for validation purposes by planning authorities. The often-exhaustive list of validation requirements frequently includes information which is not essential to the application’s validation and registration. Additional information often appears requested to slow up the rate of registration thereby relieving pressure on the authority’s development management team as throughput from the validation procedure can be regulated.

Validation requirements do need careful management however the key issue is then how to speed up the application process, make it far more predictable (to reduce the high cost of risk) and provide sufficient qualified staff resources to process and determine applications.

There have been so many reports and recommendations and previous “hand wringing” exercises aimed at providing solutions. Few. If any, have looked at de-politicising the planning process.

Many attendances at various planning committees across England have left me with the clear impression that far too few committee members are familiar with the way the system works, their legal duties and responsibilities under planning law, the cost associated with the preparation of applications, and the scale of costs associated with the appeal process. The latter is rarely revealed in the public domain particularly when an authority has appeal costs awarded in favour of an appellant which then has to be met by the “cash-strapped” authority found guilty of unreasonable behaviour.

It is also apparent that few committee chairpersons are adequately trained and really understand the principles of chair’ship. That, coupled with often reluctant officer intervention and guidance, reveals another need for training. Therefore, one of my key principles would be to ensure that all elected members attending planning committees be required to undergo meaningful training. Similarly, those officers advising committees ought to be adequately trained and encouraged to intervene with chair’ship support when members go astray or are in need of advice.

The packed public gallery dilemma is one familiar to most planning committee members. This can be orchestrated with the sole purpose of intimidating the committee. It is also notable that elected members enjoy the opportunity to “grandstand” before such an audience. There needs to be a national code of conduct applied to those interested parties attending planning (and potentially other) committees which is made public through the local authority web sites.

Applauding, heckling, booing and cheering are more akin to the local pantomime than to the forum of a planning committee which ought to be accorded gravitas for the proper conduct of discussion and decision-taking. The aim is not to stifle democratic decision-taking but to deliver responsible democratic decision-taking.

Example of Protesters at Planning Committees

A new NPPF will inevitably follow the next general election. Any new national administration will be facing the current housing crisis which is seriously harming the socio-economic prospects of the nation. Improvements must be made to the current planning system if society is to be provided with the homes it knows it needs. If Labour is that administration and is in support of “the builders and not the blockers” it needs to tackle the resourcing of planning (including the statutory consultees), the creation of a positive culture within the planning system, reduce the often unnecessarily onerous and costly validation requirements for applications and require the meaningful training of planning committee members and those officers who advise them.

[1] This is the fifth full revision since first published in March 2012.